I first

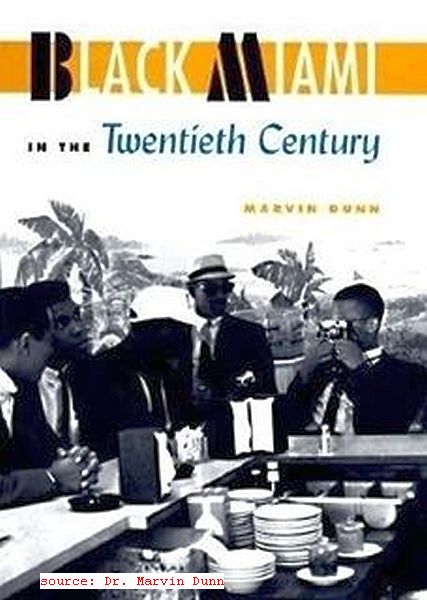

heard the name Dr. Marvin Dunn in 2016 from my late first Cousin

Mr. Kenneth Jerome Curtis who, like me, was born in Miami-Dade

County. He, like his late father (my Uncle) Isreal

Curtis worked for the once behemoth Miami Herald Newspaper in the

pressroom. My Uncle, according to my Aunt Enid (his sister), was exposed to racist

comments daily as he was the first Black/African-American to be hired in

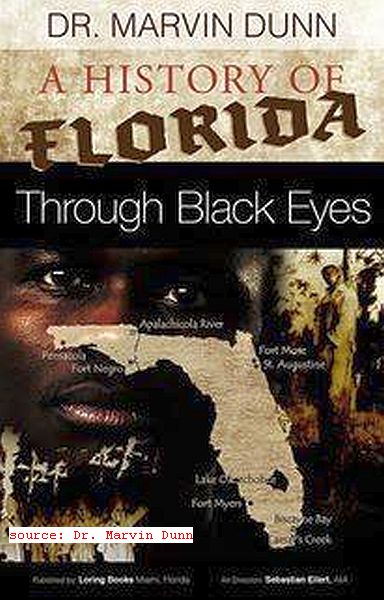

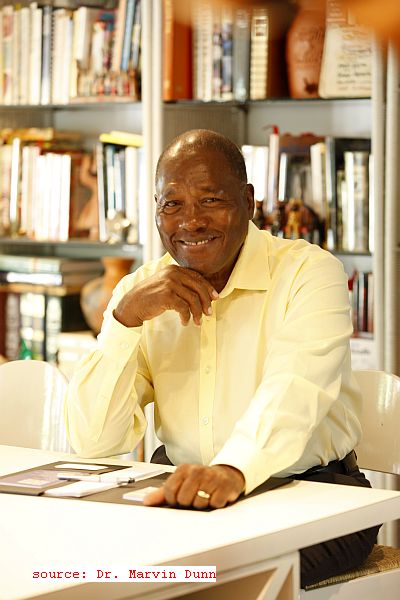

that job which paid very well. As faith would have it, I began following Dr.

Dunn on Social Media and became really impressed with his veracity

in telling it like it is/was concerning Black history as it relates to Florida

and Miami. I decided to finally reach out to him after reading about his

Tell The Truth Tour to the now infamous former thriving Black

community known as Rosewood which was the feature of a popular movie starring Award-winning actor Don Cheadle in 1997. Dr. Dunn

responded promptly after I explained to him the impetus of my interview as it

related to his upcoming historic trip to northwestern Florida where he

now owns a piece of property in the old Rosewood community. Our

telephone interview was as expected; candid, insightful, and much needed in a

country where the truth is now under constant attack from very high places.

I first

heard the name Dr. Marvin Dunn in 2016 from my late first Cousin

Mr. Kenneth Jerome Curtis who, like me, was born in Miami-Dade

County. He, like his late father (my Uncle) Isreal

Curtis worked for the once behemoth Miami Herald Newspaper in the

pressroom. My Uncle, according to my Aunt Enid (his sister), was exposed to racist

comments daily as he was the first Black/African-American to be hired in

that job which paid very well. As faith would have it, I began following Dr.

Dunn on Social Media and became really impressed with his veracity

in telling it like it is/was concerning Black history as it relates to Florida

and Miami. I decided to finally reach out to him after reading about his

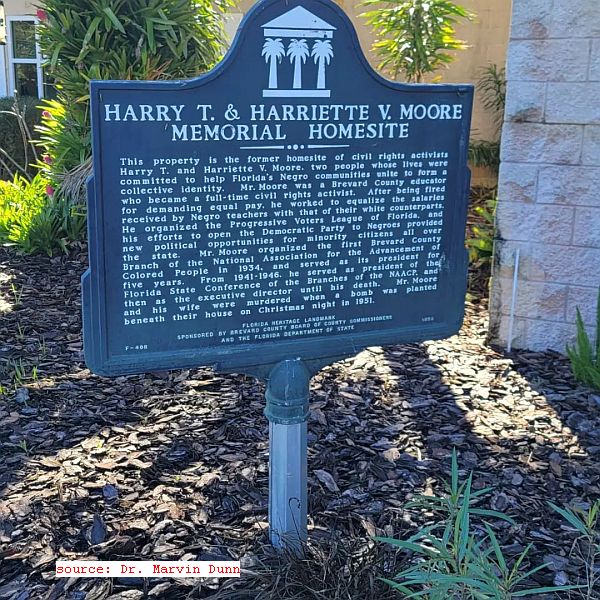

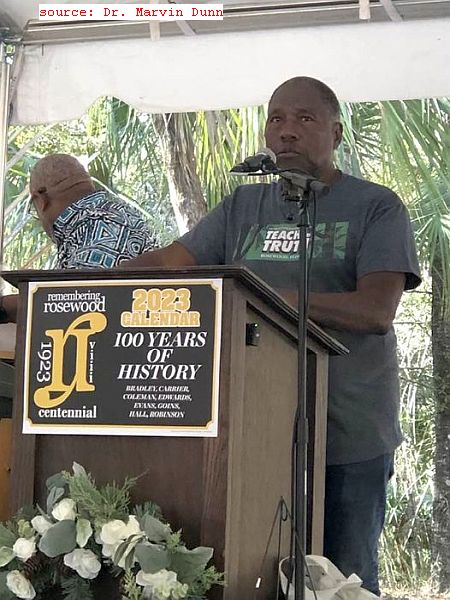

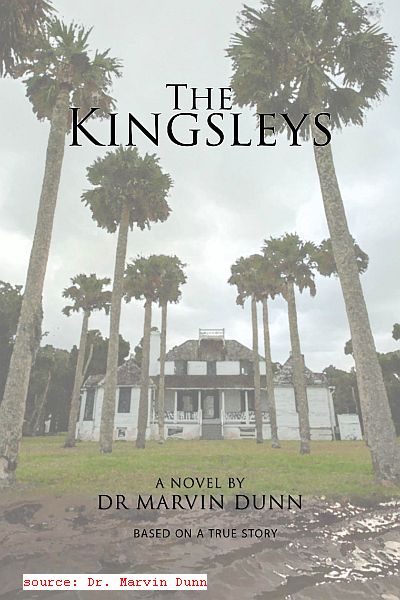

Tell The Truth Tour to the now infamous former thriving Black

community known as Rosewood which was the feature of a popular movie starring Award-winning actor Don Cheadle in 1997. Dr. Dunn

responded promptly after I explained to him the impetus of my interview as it

related to his upcoming historic trip to northwestern Florida where he

now owns a piece of property in the old Rosewood community. Our

telephone interview was as expected; candid, insightful, and much needed in a

country where the truth is now under constant attack from very high places.Note: Click here for an expanded audio interview with commentary (some adult language used)!

Jay -- Where were you born?

Jay -- Where were you born?Dr. Dunn -- I was born in Deland Florida; that's in Volusia County, Central Florida; it's about 40 miles [northeast] from Orlando.

Jay -- What was your experience with race relations while growing up before you turned 19?

Dr. Dunn -- There were no race relations. You stayed in your place, you did the

jobs that they allowed you to do, you stood in line and waited for white folks

to be served first; you sat on the back of the bus, you went to segregated

schools; you could not go into a restaurant. I was in college before I went to

the first restaurant. I had perfect teeth, not a single cavity (chuckles). A

year later I had some 15 to 20 cavities in my mouth my first year at Morehouse

(Atlanta). What was it like (growing up in Deland); it was a low aspiration existence;

you didn't aspire for much because you didn't see much to aspire to; so, my

life growing up in Volusia County and even in Miami, my family moved to Miami

in 1951, which was about the same thing; it was a sense of very severe limitedness

as to where I could go; particularly educationally. I never thought that I

could aspire to go any other place other than Bethune Cookman College (Daytona

Beach, Florida), or FAMU (Florida Agricultural & Mechanical University;

Tallahassee, Florida). It was kind of a limited existence because you did not

aspire to much because you didn't see much to aspire to.

Dr. Dunn -- There were no race relations. You stayed in your place, you did the

jobs that they allowed you to do, you stood in line and waited for white folks

to be served first; you sat on the back of the bus, you went to segregated

schools; you could not go into a restaurant. I was in college before I went to

the first restaurant. I had perfect teeth, not a single cavity (chuckles). A

year later I had some 15 to 20 cavities in my mouth my first year at Morehouse

(Atlanta). What was it like (growing up in Deland); it was a low aspiration existence;

you didn't aspire for much because you didn't see much to aspire to; so, my

life growing up in Volusia County and even in Miami, my family moved to Miami

in 1951, which was about the same thing; it was a sense of very severe limitedness

as to where I could go; particularly educationally. I never thought that I

could aspire to go any other place other than Bethune Cookman College (Daytona

Beach, Florida), or FAMU (Florida Agricultural & Mechanical University;

Tallahassee, Florida). It was kind of a limited existence because you did not

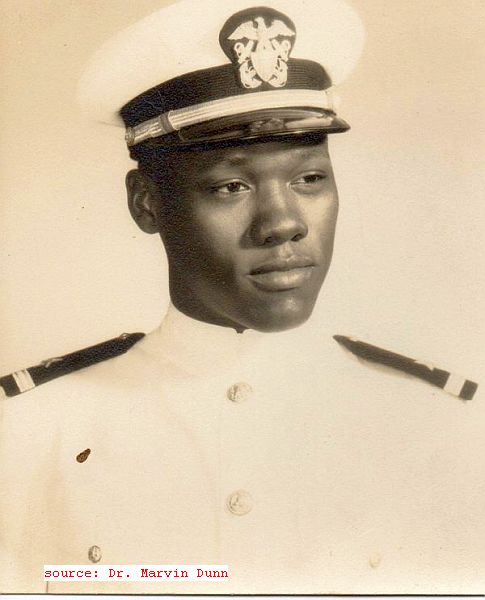

aspire to much because you didn't see much to aspire to. Jay -- Why and when did you join the United States NAVY as an

officer?

Jay -- Why and when did you join the United States NAVY as an

officer?Dr. Dunn -- My father was in the Navy; he was a cook or steward in the Navy; that was my first taste of interest in the Navy. And my older brother, two years older than I, joined the navy; and I sort of followed in that path. My intention in joining was to be a Naval Officer, not a cook or steward. I got those gold bars which meant a lot; that was my goal. It didn't quite work out that way at first.

Jay -- What was your rank and how long did your serve in the Navy (Active

and Reserve)?

Jay -- What was your rank and how long did your serve in the Navy (Active

and Reserve)?Dr. Dunn -- I was a Lieutenant; in the Army that's equal to a Captain in rank. I went in in [19] 61 and got out in [19] 66; a little over five years.

Jay -- What was your experience with race relations while serving in the Navy?

Dr. Dunn -- The Navy sent me and about 12 white guys on a Greyhound Bus; I was

the only Black person, and since I had a college degree, they put me in charge

of the group to go up to be inducted in Jacksonville (north Florida). We got to

Jacksonville, I had the papers (orders) for the group, I gave them to the petty

officer (Corporal to Staff Sergeant, Army) there at the desk; it was close to

closing time for the day so they called up the 11 or 12 white guys and gave

them tickets to allow them to go across the street to a white hotel, the rooms

to that hotel are still standing actually, for lodging that the Navy paid for

and food, to come back the next morning to begin testing for induction. And

after the white guys were gone, he called me up and gave me a ticket to go

across the railroad tracks to a Colored (today Black/African-American) rooming

house to stay overnight and come back the next day; and I said they went across

the street, and he said; well, we are closing and come back the next day.

Dr. Dunn -- The Navy sent me and about 12 white guys on a Greyhound Bus; I was

the only Black person, and since I had a college degree, they put me in charge

of the group to go up to be inducted in Jacksonville (north Florida). We got to

Jacksonville, I had the papers (orders) for the group, I gave them to the petty

officer (Corporal to Staff Sergeant, Army) there at the desk; it was close to

closing time for the day so they called up the 11 or 12 white guys and gave

them tickets to allow them to go across the street to a white hotel, the rooms

to that hotel are still standing actually, for lodging that the Navy paid for

and food, to come back the next morning to begin testing for induction. And

after the white guys were gone, he called me up and gave me a ticket to go

across the railroad tracks to a Colored (today Black/African-American) rooming

house to stay overnight and come back the next day; and I said they went across

the street, and he said; well, we are closing and come back the next day.  I walked across the railroad tracks to this rooming house; it

was a w@#$e house, there were w@#$%s on the porch when I got there; I went into

the kitchen and there were roaches. The meal was over, I got there after

dinner, but I saw roaches crawling over the table. And I went upstairs, I

didn't eat; my bed had chinks, I pulled the covers back and I could see bugs in

the seams of the pillows. And the sheets were yellow, so I slept on the chair.

There were women bringing men in all night. The next morning, I go down for

breakfast and its cold oatmeal and again flies and roaches; I didn't eat

breakfast. I go back to the induction center to take the test for Officer

Candidate School (OCS); since I was a college graduate, I was qualified to take

the OCS test, and I did; and I failed. I failed badly. So, the petty officer,

the white guy, called me up, and he is almost smiling. [He said]; You're the

college graduate right; Going to OCS? I said yes, I am, he said no you're not.

Because you failed the test; you're going to Great Lakes Recruit Training

Command (North Chicago, Illinois) with the rest of these dummies you brought in

here.

I walked across the railroad tracks to this rooming house; it

was a w@#$e house, there were w@#$%s on the porch when I got there; I went into

the kitchen and there were roaches. The meal was over, I got there after

dinner, but I saw roaches crawling over the table. And I went upstairs, I

didn't eat; my bed had chinks, I pulled the covers back and I could see bugs in

the seams of the pillows. And the sheets were yellow, so I slept on the chair.

There were women bringing men in all night. The next morning, I go down for

breakfast and its cold oatmeal and again flies and roaches; I didn't eat

breakfast. I go back to the induction center to take the test for Officer

Candidate School (OCS); since I was a college graduate, I was qualified to take

the OCS test, and I did; and I failed. I failed badly. So, the petty officer,

the white guy, called me up, and he is almost smiling. [He said]; You're the

college graduate right; Going to OCS? I said yes, I am, he said no you're not.

Because you failed the test; you're going to Great Lakes Recruit Training

Command (North Chicago, Illinois) with the rest of these dummies you brought in

here.